Promoting economic progress and reducing poverty in policymakers and lenders. They are taking a fresh look at urban development. Population expansion, urban sprawl, “failures” in planning, illegal encroachment, and “good governance” reforms are all contributing factors in Social Housing. Institutional reports and scientific studies on African cities frequently address the same topics.

As a result, urban operations have become considerably more scarce; a relative “urban rebound” has occurred since the 2000s. In the 1980s, the early optimism of independence faded away. State engagement across the board was reduced in the 1990s due to a series of structural adjustment programs.

Many stakeholders, including state officials, have reactivated or launched development projects. A new “social” property development and house building initiatives have been launched. I am analyzing policy changes in the field of real estate since the country’s declaration of independence.

Our focus will be on “Social Housing” ideologies and measures as well as their execution. These public intervention strategies offer cheap housing for lower-income families by utilizing the “social” category.

But our investigation demonstrates the feature of the home-generated is not always apparent. Moving from a “modern” city to one that has been “adjusted.” At this time, domestic construction companies began building residential towers based on the Athens Charter. Often at the request of the French government.

The creation of a few estates and a few apartment buildings for civil servants was the extent of housing policy during colonial times. Social Housing has been a symbol of “modernity” in the newly independent countries. This lodging was created to help the “contemporary” city inhabitant break away from the “traditional” ways of life. These initiatives were primarily designed to house civil servants in each of the countries involved. Affordability was limited to those in the middle and upper classes because of the high cost of the homes.

Even though these programs marked the beginning of state intervention in the housing industry, they did not help the poorest households. Banks and other financial institutions soon reacted forcefully in the face of these heavily subsidized enterprises, led by insolvent nations and often favoring local clientele.

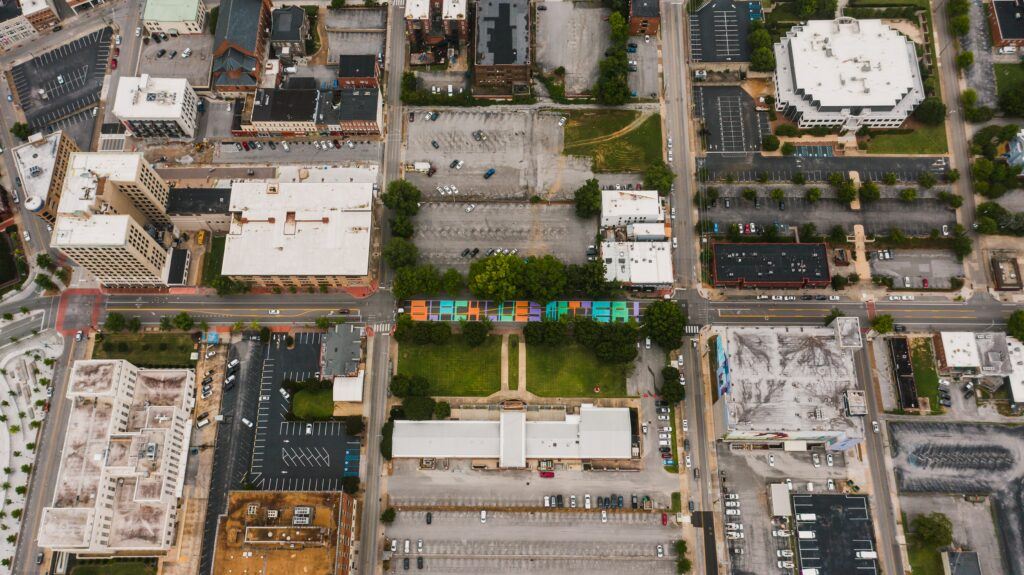

An urban interventionist approach was put out of its misery by structural adjustment plans. Privatization, transfer, or sale of public housing to current residents occurred. At the same time, people were mainly responsible for maintaining communal areas. It is to reach the “global” city and Yaoundé has been the site of “resettlement” operations that have not relocated residents.

The “ancient town” of Nouakchott was demolished in 2009 to erect skyscrapers in its place. It is pushed for attempts to improve competitiveness and draw in international investment. The poorest residents of the city are routinely evicted as a result of large-scale construction projects. Many of the city’s older neighborhoods are in danger of being restructured, but no one knows what that would entail or how much it will cost the locals.

Mauritania is actively seeking financial assistance from the Gulf states. According to expert studies, the “prosperous” city should not forget to be an “inclusive” city. Its programs are launched in tandem with these vast developments. Through public-private partnership funding structures that may not always be as open as they should be.

In light of the state’s limited investment capacity, these are deemed vital and are made possible by the increasing number of investors. In Cameroon, a plan to build 10,000 homes and develop 50,000 building lots was expected to be completed by 2013. The creation of high-end apartment complexes for house ownership has been the most common outcome.

Even though Chinese corporations are technically in the process of forming relationships with the company. Future construction projects will be less expensive and more accessible as a result. These public-private partnerships are geared toward the middle and upper classes, displacing others who are less financially secure.

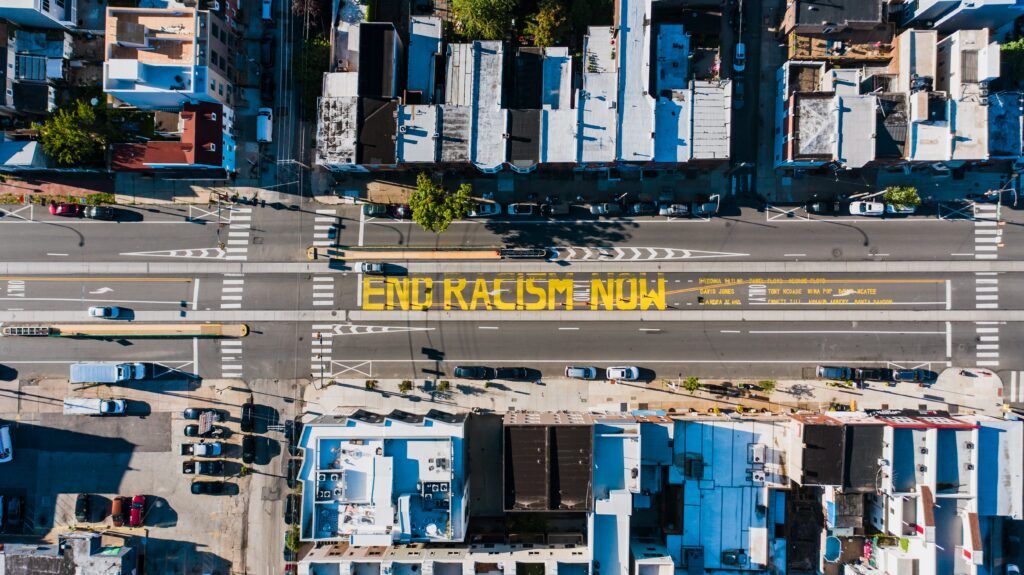

Despite being marketed as “Social Housing,” these new efforts nevertheless target the wealthiest members of society. New housing policies, depending on participation, are attempting to offer an alternative.

Social Housing as a means of reinvention, can “citizen engagement” be used as an effective tool?

As a first step in encouraging people to build their own homes, this “bricks and mortar” approach was designed to improve urban integration. Since “the highest international authorities can foster citizen engagement,” it covers many scenarios. It started in the blue and was sparked by residents.

We’ve also seen a reinvention of housing cooperatives due to these programs influenced by lenders’ guidance. The programs encourage construction of new homes and bring city people together in legalized structures that cut the cost of housing.

In the 1950s and 1960s, the Castors movement in France transferred its expertise to Dakar, Senegal, a city in West Africa. “Exemplary” is the cooperative’s goal, and it aims to be an early proponent of public policy in the area of social housing. It’s not so much a call to action as it is a sign of progress.

Public involvement in the search for solutions will benefit from an alternate kind of dwelling. Development of a new subject of study. In the beginning, the state intervenes, followed by a period of disengagement and implementation of a self-building program.

Social Housing is based on localized experience, who is responsible for inspiring and propagating these policies?

The peculiar conditions of the Sankara years aside, we may ponder if there are any differences between towns in sub-Saharan Africa. From a historical and geographic standpoint, new empirical investigations are needed more than ever. Findings from Africa aren’t unique to the debate over whether or not housing should be provided to the poorest members of society.

Throughout Europe, where states are likewise currently searching for the optimal model, is a vast diversity of populations. Last but not least, this comparative reading shows how successive initiatives intended to develop Social Housing have failed to achieve their stated goals.

It was primarily aimed at affluent homes while remaining mostly inaccessible to others in less fortunate circumstances. This is followed by the creation of public-private partnerships and local initiatives financed by non-profit organizations.